Pilgrimage to the White Valley

Skiing Chamonix's Vallee Blanche

October 31, 2004

| ||

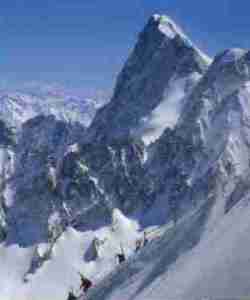

| The Vallee Blanche Photo by Lisa Auer |

||

On my first visit to Chamonix, it was not until the morning of the third day that the clouds broke revealing a skyline clean and jagged as an eggshell. The mountains appeared two-dimensional, drawn ever upwards onto the azure canvas stretch of the sky. I wandered the streets mouth agape, spellbound for the day, munching on croissants and colliding with lampposts. After that first visit to Chamonix in 1996, part of me never left. I had mentally moved in.

For six months of the year, between December and May, thousands of people from around the globe congregate on the Vallée Blanche, the white valley at the foot of Mont Blanc in Chamonix, France.

It is not a pilgrimage associated with the birthplace of Mohammed, or medieval refuges, or fields of bright yellow sunflowers that pollinate your shoulders as you brush past, or indeed of any religious significance, though some would claim to have had a spiritual experience along the way.

The Vallée Blanche is the most famous lift-accessed ski descent in the world. In a good year it sweeps for 25 kilometres of mainly intermediate terrain, meandering down glaciers and threading through crevasse fields towards the bars of Chamonix. It is a journey out-of-bounds and out of the ordinaire. Starting at 3800 metres some also find it noticeably thin on air.

Usually accomplished in a day, accompanied by a guide, it is a modern day pilgrimage made possible by a mad wager taken in the 1950's by the daring Italian engineer, Dino Lora Totino, Count of Cervinia. He took on the formidable challenge to connect in two sections, Chamonix at 1000 metres to the precipitous 3842-metre summit pinnacle of the Aiguille du Midi (the needle of the south). This was well before the dashing ease of helicopters. The Herculean task began with a caravan of thirty mountaineers who hoisted nearly two kilometres of cable up to the top. In six years the highest funicular in the world was completed.

Viewed from Chamonix, within a wraparound skyline bristling with rocky gendarmes, granite spires and stiletto pillars, the Aiguille du Midi seems positively hypodermic. A slither of rock so thin it defies nature – in fact, it is completely artificial. A metal mast that serves as a television relay station crowns the man made fortress, a hybrid of medieval architecture and James Bond film set that has been carved directly into the granite of the Piton Nord and Piton Central (the summit towers).

In addition to housing the terminal station of the téléphérique (cable car), Totino's cliff-top castle boasts all the tourist trappings of the tallest skyscraper in your average city. There's a thirty seat à la carte restaurant, a cafeteria, a couple of snack bars, a panoramic viewing terrace with coin-operated binoculars honed in on Mont Blanc, a souvenir shop selling postcards and tiny replica cable cars, toilet and telephone facilities and a warren of catwalks and tunnels.

"The Vallée Blanche starts on the perilously exposed ridgeline, which leads out at an intrepid boot-width for a hundred metres..." |

The Aiguille du Midi téléphérique has the capacity to transport about 650 mountain-bound souls every hour. Needless to say, during peak seasons - Christmas and Easter - the queues can be serious. However, don't despair, just look around. The Chamonix station of the Midi, as it is known, is one of the most fascinating people-watching venues of all time.

Clustered together, jostling in queues - with the fetid aroma of stale coffee and pain au chocolat - then unceremoniously sardine-packed into cable car after cable car you will find: keen skiers and snowboarders almost bursting their Gortex seams to hit the slopes, local guides with their distinctive uniforms (and airs - like those of an Ibex bull that has just been disturbed on home turf), business travellers in shirt and tie who only reluctantly leave behind their briefcases, near bus loads of Japanese tourists armed with the latest Nikon or Leica camera, intrepid mountaineers in threadbare Polypro, and glamorous women in fur coats adorned with such dazzling jewels that vie for attention with the star-spangled glint of the glaciers.

On hand accessories range from snowboards, skis, poles, ice axes and crampons to snakeskin handbags, lipstick cases, mobile phones and parasols. I often cringe in horror at the paradox of all those freshly pedicured toes daintily clad in the finest of Italian leathers mingling dangerously with oversized clomping boots.

The téléphérique makes the high mountains accessible to just about everyone. It has rewritten the nature of climbing in Chamonix by providing even the laziest mountaineer ready access to the heart of the massif. It is not recommended, however, for children under two or people with heart problems.

Looking closely out the window during the eight minute ride up from Chamonix to the Plan d'Aiguille, the mid station of the cable car, you may be lucky enough in spring to spot a couple of cavorting chamois or a family of fossiking marmots. From the high mountain pastures of the Plan d'Aiguille (they still bring sheep up there in summer) you can view all the vegetation zones from forest to scrubland and alpine grasslands to moraine and glaciers, providing that it isn't all covered in snow.

A pair of gossamer threads that loop in uninterrupted strands over 1500 metres long link the improbable edifice of the Aiguille du Midi with the mid station at the mountains' foot. Chamonix specializes in hyperbole. It boasts (among other things) that to this day, their lift system is the longest single span in the world. And indeed it is.

It takes another eight minutes of 'oohing' and 'aahing' to get to the top. The exhilarating flight takes you over the seracs and hanging glacier of Les Pélerins and gives a bird's eye tour of the Aiguille du Midi's sheer North wall - a cliff as cold and forbidding as any Eiger nightmare. Every wrinkle and fold of rock and ice has been climbed there, and every imaginable snowy chute has also been skied or snowboarded.

From the top of the Midi, Mont Blanc looms a great distant orb. Even when the high mountains are shrouded in cloud, Chamonix is dominated by the overwhelming presence of Mont Blanc - both physically and historically. It is not a classically splendid looking peak like the Swiss Matterhorn, but it appears as a great, glazed meringue that garnishes the glaciers far above the cobblestones of Chamonix. Mont Blanc has over the years inspired poetry, madness and even the creation of Frankenstein!

Back in the early 1800's, Lord Byron described Mont Blanc as

"...the monarch of mountains;

They crowned him long ago

On a throne of rocks, in a robe of clouds,

With a diadem of snow' (Manfred - Act I, Scene I)

During the same period, another of the British romantic poets, Shelley, experienced an 'undisciplined overflowing of the soul' in the presence of Mont Blanc and a 'sentiment of ecstatic wonder not unallied to madness'. His wife, Mary Shelley, developed an infatuation with ice in Chamonix that later inspired her creation of Frankenstein.

For many centuries, remaining unconquered in spite of numerous summit attempts, Mont Blanc kept the Priorie of Chamonix captivated by an aura of mystery and inaccessibility. In the early 1500's before ventures at altitude had been made into the Himalaya it was thought that a night out, high on a mountain, would mean certain death. Mont Blanc was envisaged as the stomping ground of dragons, witches and all kinds of mythic beasts.

In 1786 the summit of Mont Blanc at 4807 metres was finally conquered (after more than 20 years of attempts) when Michel-Gabriel Paccard, a local doctor with a scientific bent, and Jacques Balmat, an ambitious crystal gatherer, became the first men to stand on the highest mountain in Europe west of the Caucuses. This feat brought international acclaim to the modest pastoral town of Chamonix and a steady stream of tourists was to follow to attempt the illustrious peak. Today more than 2000 people climb to the top each year and as a result Chamonix has evolved as a major tourist centre.

People shod in street shoes end their journey at the top of the 'Midi', taking a downward cable car home. For those who would like to experience the ski descent of their life, so begins the Vallée Blanche.

The Vallée Blanche starts on the perilously exposed ridgeline, which leads out at an intrepid boot-width for a hundred metres from the Aiguille du Midi lift station. Most people descend this section on foot. An alarming drop-off to the left over the vertiginous north face is slenderly protected by a rope railing before the route turns gently right towards Mt Blanc and into the heart of the massif. There's a nice basketball court-sized flat spot to click into your bindings, adjust your goggles and regain your equilibrium, then WHOOSH...relax and enjoy the ride.

As you proceed down the slope, turns unfurling, gently at first, so too history unravels. Each couloir and rock buttress, glacier and col is coloured by the stories of the daring exploits of mountaineers, skiers, scientists, hunters and crystal gatherers - a romantic collection of fairytale characters that would make the life of your average Hollywood heartthrob seem dull.